Linked Lists in Python

By Dan Bader

Learn how to implement a linked list data structure in Python, using only built-in data types and functionality from the standard library.

Every Python programmer should know about linked lists:

They are among the simplest and most common data structures used in programming.

So, if you ever found yourself wondering, “Does Python have a built-in or ‘native’ linked list data structure?” or, “How do I write a linked list in Python?” then this tutorial will help you.

Python doesn’t ship with a built-in linked list data type in the “classical” sense. Python’s list type is implemented as a dynamic array—which means it doesn’t suit the typical scenarios where you’d want to use a “proper” linked list data structure for performance reasons.

Please note that this tutorial only considers linked list implementations that work on a “plain vanilla” Python install. I’m leaving out third-party packages intentionally. They don’t apply during coding interviews and it’s difficult to keep an up-to-date list that considers all packages available on Python packaging repositories.

Before we get into the weeds and look at linked list implementations in Python, let’s do a quick recap of what a linked list data structure is—and how it compares to an array.

What are the characteristics of a linked list?

A linked list is an ordered collection of values. Linked lists are similar to arrays in the sense that they contain objects in a linear order. However they differ from arrays in their memory layout.

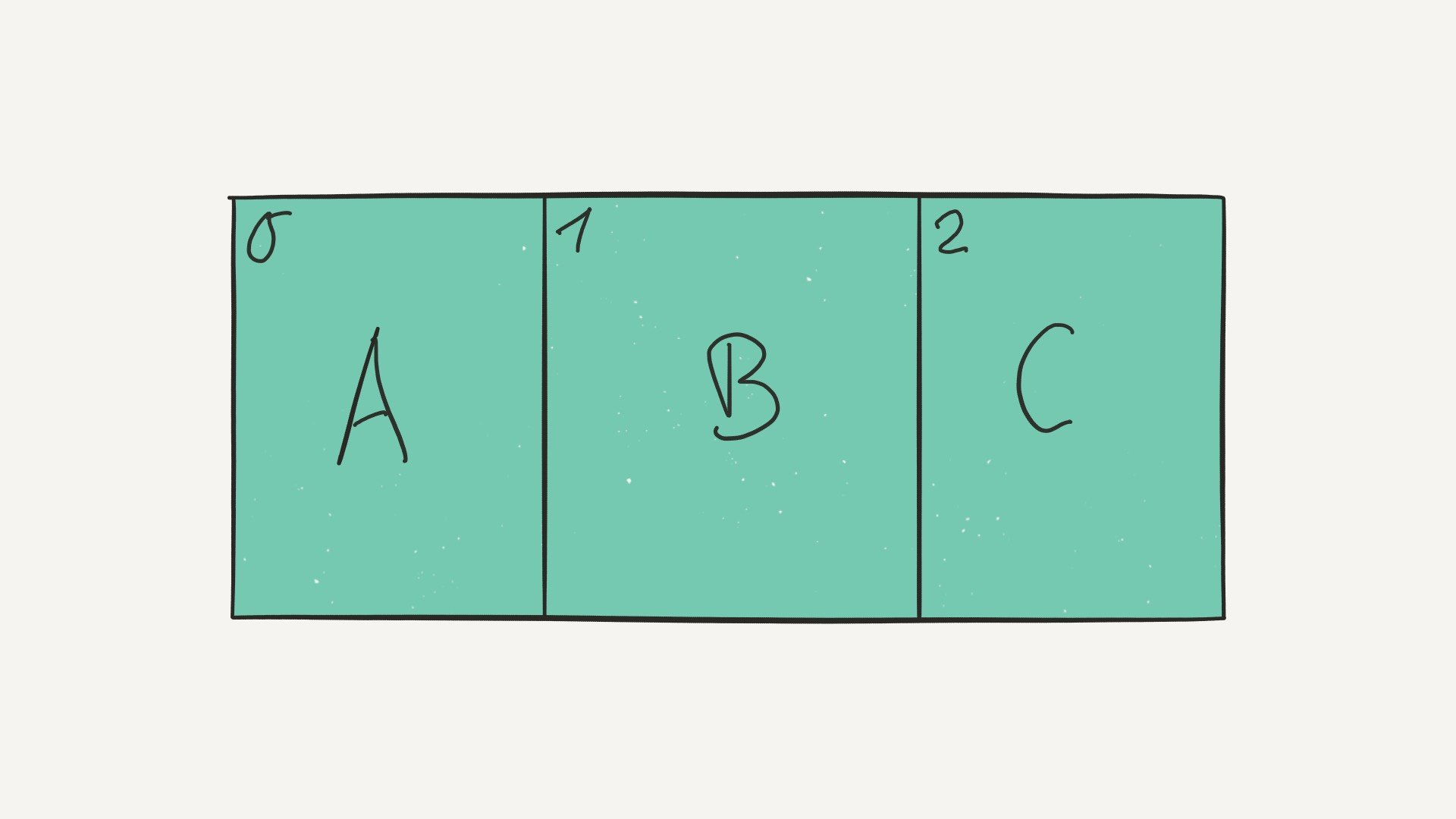

Arrays are contiguous data structures and they’re composed of fixed-size data records stored in adjoining blocks of memory. In an array, data is tightly packed—and we know the size of each data record which allows us to quickly look up an element given its index in the array:

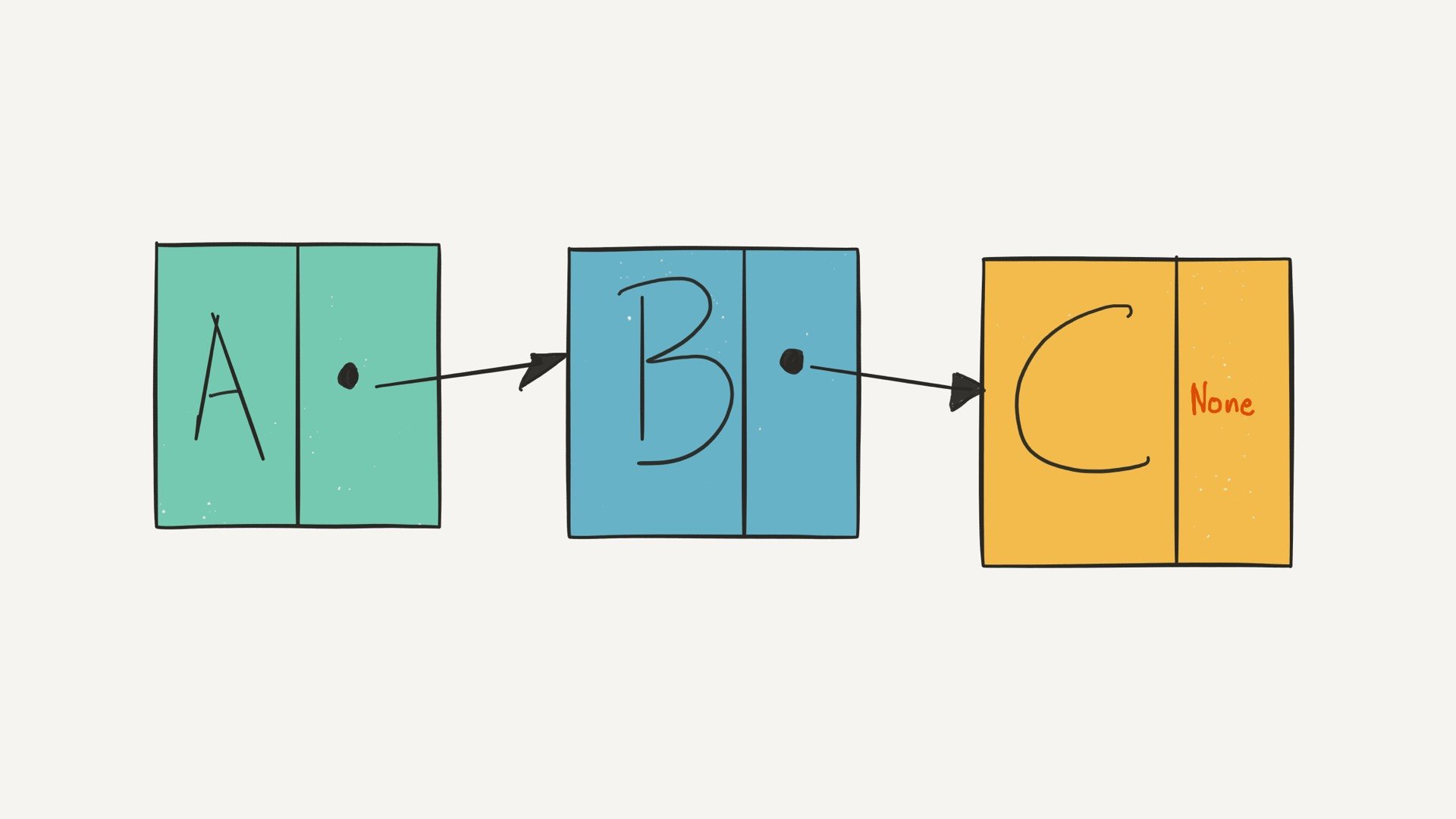

Linked lists, however, are made up of data records linked together by pointers. This means that the data records that hold the actual “data payload” can be stored anywhere in memory—what creates the linear ordering is how each data record “points” to the next one:

There are two different kinds of linked lists: singly-linked lists and doubly-linked lists. What you saw in the previous example was a singly-linked list—each element in it has a reference to (a “pointer”) to the next element in the list.

In a doubly-linked list, each element has a reference to both the next and the previous element. Why is this useful? Having a reference to the previous element can speed up some operations, like removing (“unlinking”) an element from a list or traversing the list in reverse order.

How do linked lists and arrays compare performance-wise?

You just saw how linked lists and arrays use different data layouts behind the scenes to store information. This data layout difference reflects in the performance characteristics of linked lists and arrays:

Element Insertion & Removal: Inserting and removing elements from a (doubly) linked list has time complexity O(1), whereas doing the same on an array requires an O(n) copy operation in the worst case. On a linked list we can simply “hook in” a new element anywhere we want by adjusting the pointers from one data record to the next. On an array we have to allocate a bigger storage area first and copy around the existing elements, leaving a blank space to insert the new element into.

Element Lookup: Similarly, looking up an element given its index is a slow O(n) time operation on a linked list—but a fast O(1) lookup on an array. With a linked list we must jump from element to element and search the structure from the “head” of the list to find the index we want. But with an array we can calculate the exact address of an element in memory based on its index and the (fixed) size of each data record.

Memory Efficiency: Because the data stored in arrays is tightly packed they’re generally more space-efficient than linked lists. This mostly applies to static arrays, however. Dynamic arrays typically over-allocate their backing store slightly to speed up element insertions in the average case, thus increasing the memory footprint.

Now, how does this performance difference come into play with Python? Remember that Python’s built-in list type is in fact a dynamic array. This means the performance differences we just discussed apply to it. Likewise, Python’s immutable tuple data type can be considered a static array in this case—with similar performance trade-offs compared to a proper linked list.

Does Python have a built-in or “native” linked list data structure?

Let’s come back to the original question. If you want to use a linked list in Python, is there a built-in data type you can use directly?

The answer is: “It depends.”

As of Python 3.6 (CPython), doesn’t provide a dedicated linked list data type. There’s nothing like Java’s LinkedList built into Python or into the Python standard library.

Python does however include the collections.deque class which provides a double-ended queue and is implemented as a doubly-linked list internally. Under some specific circumstances you might be able to use it as a “makeshift” linked list. If that’s not an option you’ll need to write your own linked list implementation from scratch.

How do I write a linked list using Python?

If you want to stick with functionality built into the core language and into the Python standard library you have two options for implementing a linked list:

You could either use the

collections.dequeclass from the Python standard library and take advantage of the fact that it’s implemented as a doubly-linked list behind the scenes. But this will only work for some use cases—I’ll go into more details on that further down in the article.Alternatively, you could define your own linked list type in Python by writing it from scratch using other built-in data types. You’d implement your own custom linked list class or base your implementation of Lisp-style chains of

tupleobjects. Again, see below for more details.

Now that we’ve covered some general questions on linked lists and their availability in Python, read on for examples of how to make both of the above approaches work.

Option 1: Using collections.deque as a Linked List

collections.deque as a Linked ListThis approach might seem a little odd at first because the collections.dequeclass implements a double-ended queue, and it’s typically used as the go-to stack or queue implementation in Python.

But using this class as a “makeshift” linked list might make sense under some circumstances. You see, CPython’s deque is powered by a doubly-linked list behind the scenes and it provides a full “list-like” set of functionality.

Under some circumstances, this makes treating deque objects as linked list replacements a valid option. Here are some of the key performance characteristics of this approach:

Inserting and removing elements at the front and back of a

dequeis a fast O(1) operation. However, inserting or removing in the middle takes O(n)time because we don’t have access to the previous-element or next-element linked list pointers. That’s abstracted away by thedequeinterface.Storage is O(n)—but not every element gets its own list node. The

dequeclass uses blocks that hold multiple elements at once and then these blocks are linked together as a doubly-linked list. As of CPython 3.6 the block size is 64 elements. This incurs some space overhead but retains the general performance characteristics given a large enough number of elements.In-place reversal: In Python 3.2+ the elements in a

dequeinstance can be reversed in-place with thereverse()method. This takes O(n) time and no extra space.

Using collections.deque as a linked list in Python can be a valid choice if you mostly care about insertion performance at the beginning or the end of the list, and you don’t need access to the previous-element and next-element pointers on each object directly.

Don’t use a deque if you need O(1) performance when removing elements. Removing elements by key or by index requires an O(n) search, even if you have already have a reference to the element to be removed. This is the main downside of using a deque like a linked list.

If you’re looking for a linked list in Python because you want to implement queues or a stacks then a deque is a great choice, however.

Here are some examples on how you can use Python’s deque class as a replacement for a linked list:

Option 2: Writing Your Own Python Linked Lists

If you need full control over the layout of each linked list node then there’s no perfect solution available in the Python standard library. If you want to stick with the standard library and built-in data types then writing your own linked list is your best bet.

You’ll have to make a choice between implementing a singly-linked or a doubly-linked list. I’ll give examples of both, including some of the common operations like how to search for elements, or how to reverse a linked list.

Let’s take a look at two concrete Python linked list examples. One for a singly-linked list, and one for a double-linked list.

✅ A Singly-Linked List Class in Python

Here’s how you might implement a class-based singly-linked list in Python, including some of the standard algorithms:

And here’s how you’d use this linked list class in practice:

Note that removing an element in this implementation is still an O(n) time operation, even if you already have a reference to a ListNode object.

In a singly-linked list removing an element typically requires searching the list because we need to know the previous and the next element. With a double-linked list you could write a remove_elem() method that unlinks and removes a node from the list in O(1) time.

✅ A Doubly-Linked List Class in Python

Let’s have a look at how to implement a doubly-linked list in Python. The following DoublyLinkedList class should point you in the right direction:

Here are a few examples on how to use this class. Notice how we can now remove elements in O(1) time with the remove_elem() function if we already hold a reference to the list node representing the element:

Both example for Python linked lists you saw here were class-based. An alternative approach would be to implement a Lisp-style linked list in Python using tuples as the core building blocks (“cons pairs”). Here’s a tutorial that goes into more detail: Functional Linked Lists in Python.

Python Linked Lists: Recap & Recommendations

We just looked at a number of approaches to implement a singly- and doubly-linked list in Python. You also saw some code examples of the standard operations and algorithms, for example how to reverse a linked list in-place.

You should only consider using a linked list in Python when you’ve determined that you absolutely need a linked data structure for performance reasons (or you’ve been asked to use one in a coding interview.)

In many cases the same algorithm implemented on top of Python’s highly optimized list objects will be sufficiently fast. If you know a dynamic array won’t cut it and you need a linked list, then check first if you can take advantage of Python’s built-in deque class.

If none of these options work for you, and you want to stay within the standard library, only then should you write your own Python linked list.

In an interview situation I’d also advise you to write your own implementation from scratch because that’s usually what the interviewer wants to see. However it can be beneficial to mention that collections.deque offers similar performance under the right circumstances. Good luck and…Happy Pythoning!

Read the full “Fundamental Data Structures in Python” article series here. This article is missing something or you found an error? Help a brother out and leave a comment below.

Functional linked lists in Python

By Dan Bader

Linked lists are fundamental data structures that every programmer should know. This article explains how to implement a simple linked list data type in Python using a functional programming style.

Inspiration

The excellent book Programming in Scala inspired me to play with functional programming concepts in Python. I ended up implementing a basic linked list data structure using a Lisp-like functional style that I want to share with you.

I wrote most of this using Pythonista on my iPad. Pythonista is a Python IDE-slash-scratchpad and surprisingly fun to work with. It’s great when you’re stuck without a laptop and want to explore some CS fundamentals :)

So without further ado, let’s dig into the implementation.

Constructing linked lists

Our linked list data structure consists of two fundamental building blocks: Niland cons. Nil represents the empty list and serves as a sentinel for longer lists. The cons operation extends a list at the front by inserting a new value.

The lists we construct using this method consist of nested 2-tuples. For example, the list [1, 2, 3] is represented by the expression cons(1, cons(2, cons(3, Nil))) which evaluates to the nested tuples (1, (2, (3, Nil))).

Why should we use this structure?

First, the cons operation is deeply rooted in the history of functional programming. From Lisp’s cons cells to ML’s and Scala’s :: operator, cons is everywhere – you can even use it as a verb.

Second, tuples are a convenient way to define simple data structures. For something as simple as our list building blocks, we don’t necessarily have to define a proper class. Also, it keeps this introduction short and sweet.

Third, tuples are immutable in Python which means their state cannot be modified after creation. Immutability is often a desired property because it helps you write simpler and more thread-safe code. I like this article by John Carmack where he shares his views on functional programming and immutability.

Abstracting away the tuple construction using the cons function gives us a lot of flexibility on how lists are represented internally as Python objects. For example, instead of using 2-tuples we could store our elements in a chain of anonymous functions with Python’s lambda keyword.

To write simpler tests for more complex list operations we’ll introduce the helper function lst. It allows us to define list instances using a more convenient syntax and without deeply nested cons calls.

Basic operations

All operations on linked lists can be expressed in terms of the three fundamental operations head, tail, and is_empty.

headreturns the first element of a list.tailreturns a list containing all elements except the first.is_emptyreturnsTrueif the list contains zero elements.

You’ll see later that these three operations are enough to implement a simple sorting algorithm like insertion sort.

Length and concatenation

The length operation returns the number of elements in a given list. To find the length of a list we need to scan all of its n elements. Therefore this operation has a time complexity of O(n).

concat takes two lists as arguments and concatenates them. The result of concat(xs, ys) is a new list that contains all elements in xs followed by all elements in ys. We implement the function with a simple divide and conquer algorithm.

Last, init, and list reversal

The basic operations head and tail have corresponding operations last and init. last returns the last element of a non-empty list and init returns all elements except the last one (the initial elements).

Both operations need O(n) time to compute their result. Therefore it’s a good idea to reverse a list if you frequently use last or init to access its elements. The reverse function below implements list reversal, but in a slow way that takes O(n²) time.

Prefixes and suffixes

The following operations take and drop generalize head and tail by returning arbitrary prefixes and suffixes of a list. For example, take(2, xs) returns the first two elements of the list xs whereas drop(3, xs) returns everything except the last three elements in xs.

Element selection

Random element selection on linked lists doesn’t really make sense in terms of time complexity – accessing an element at index n requires O(n) time. However, the element access operation apply is simple to implement using head and drop.

More complex examples

The three basic operations head, tail, and is_empty are all we need to implement a simple (and slow) sorting algorithm like insertion sort.

The following to_string operation flattens the recursive structure of a given list and returns a Python-style string representation of its elements. This is useful for debugging and makes for a nice little programming exercise.

Where to go from here

This article is more of a thought experiment than a guide on how to implement a useful linked list in Python. Keep in mind that the above code has severe restrictions and is not fit for real life use. For example, if you use this linked list implementation with larger example lists you’ll quickly hit recursion depth limits (CPython doesn’t optimize tail recursion).

I spent a few fun hours playing with functional programming concepts in Python and I hope I inspired you to do the same. If you want to explore functional programming in ‘real world’ Python check out the following resources:

Last updated